Analysis: IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report 2023

The U.N. plan calls for a substantial reduction in fossil fuel usage to reduce emissions, but fails to explain how to meet global energy demand.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) latest report, a summary of findings in prior reports and mitigation recommendations, purports to offer a plan to limit global warming to 1.5°Celsius. Upon the release of the report yesterday, the final major offering from IPCC until 2030, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned of a climate time bomb and argued that the report offers “a how-to guide to defuse the climate time bomb.” Guterres added, “Our world needs climate action on all fronts — everything, everywhere, all at once.” The fact that the Secretary General shoe-horned a reference to this year’s Academy Awards Best Picture winner in his remarks should demonstrate how serious this plan is.

At no point in this analysis will the science of IPCC be challenged. However, the notion that IPCC’s latest release is a “plan” will be challenged. Setting a deadline for a goal is not a plan and neither is a list of actions that must take place for the goal to be realized. Plans require guidance on execution - how to achieve deadlines and implement changes for the plan to come to fruition. Having read the previous IPCC reports that serve as the basis for this latest offering, there’s often very little detail on the “how” in any of the reports, with the possible exception of adaptation recommendations. Nothing could have made this point more salient than Guterres’ latest revisions offered the same day as the release of the “plan”:

Stepping up his pleas for action on fossil fuels, Guterres called for rich countries to accelerate their target for achieving net zero emissions to as early as 2040, and developing nations to aim for 2050 — about a decade earlier than most current targets. He also called for them to stop using coal by 2030 and 2040, respectively, and ensure carbon-free electricity generation in the developed world by 2035, meaning no gas-fired power plants either.

To his credit, Guterres does make the energy transition look easy. The solution to nations around the world falling behind on their emissions targets? Simply move the deadline up 10 years and demand all fossil fuels used for electricity disappear. Statements like this from Guterres illustrate the widespread ignorance of the degree of difficulty, and arguably the impossibility, of IPCC’s demands. Achieving the 1.5°Celsius target involves much more than electric vehicles and electricity from solar and wind. IPCC’s target requires fundamental changes in what people eat, where they live (example: living where you work helps to achieve the 1.5°Celsius goal) how they are governed, and how they build and grow everything.

IPCC and Guterres incorporate a number of false assumptions into their belief that their global energy transition plan will work. The first assumption is that a premeditated energy transition (the central planning of global energy resources) has an inherent advantage over energy transitions driven by innovation and market forces. There’s a complete absence of evidence to justify that position. Second, the U.N. assumes that climate change is a top priority for all nations. However, analysis suggests that poverty reduction, economic expansion, and geopolitical aspirations trump climate concerns in most nations. The following analysis of India, China, and Africa substantiate this claim.

Perhaps the most interesting fallacy embedded in the Guterres assumption that deadlines are fluid is the idea that expanding the use of solar, wind and batteries will reduce aggregate fossil fuel consumption. Historical data shows this not to be true. In Vaclav Smil’s “Numbers Don’t Lie” he analyzes global fossil fuel use from the first United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992) through 2017 and finds that aggregate fossil fuel usage dropped only 1.5% over the 25-year period. This historical trend is expected to continue, according to a report released last week by the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA).

EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2023 report predicts renewables will overtake fossil fuels as the primary electric power source by 2050. Yet, EIA also predicts that domestic natural gas consumption will remain stable.

Despite no significant change in domestic petroleum and other liquids consumption through 2040 across most AEO2023 cases, we expect U.S. production to remain historically high as exports of finished products grow in response to growing international demand. Despite the shift toward renewable sources and batteries in electricity generation, domestic natural gas consumption remains relatively stable—ending recent growth in most cases. Natural gas production, however, in some cases continues to grow in response to international demand for liquefied natural gas, supported by associated natural gas produced along with crude oil. Given the combination of relatively little growth in domestic consumption and continued growth in production, we project that the United States will remain a net exporter of petroleum products and natural gas through 2050 in all AEO2023 cases.

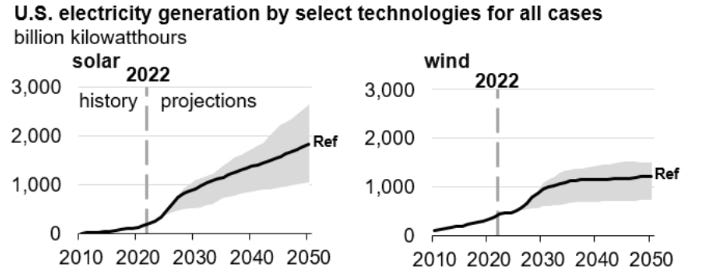

The stable (as opposed to an increase) natural gas usage rests on very aggressive growth projections for wind and solar, depicted below:

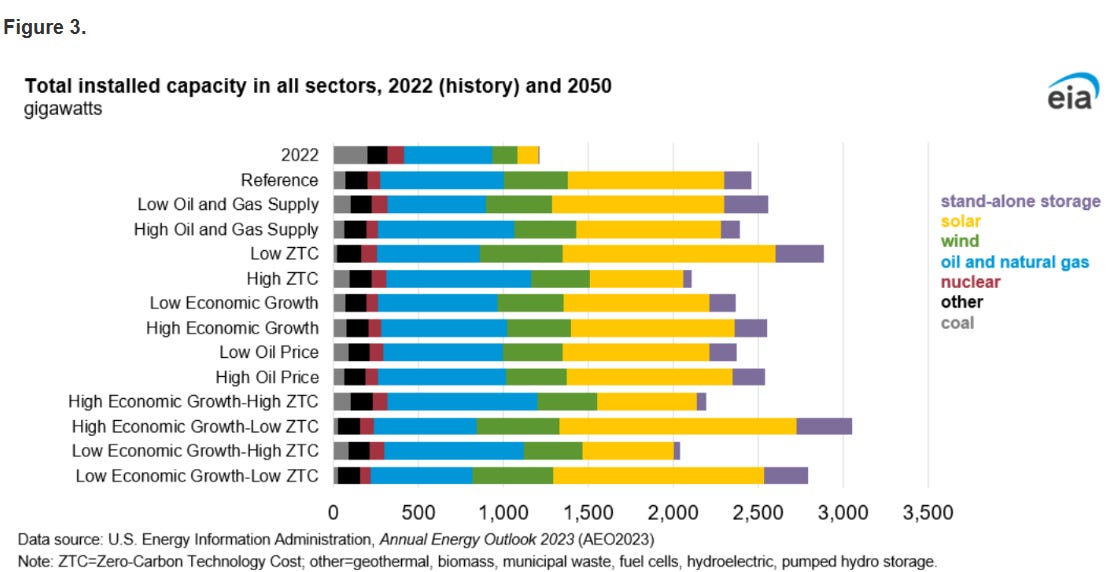

EIA also provides data on projected available capacity by source through 2050, again illustrating that not much changes for natural gas from 2022 through 2050:

The EIA data demolishes the arguments environmental NGOs sell to the media about fossil fuels. Fossil fuel usage is not a matter of choice or malevolence, it is clearly a matter of demand. Outstanding growth projections for both solar and wind will not make a dent in aggregate fossil fuel usage over the next 30 years, based on EIA’s data. IPCC and Guterres overestimate the power of central planning and global cooperation regarding this transition, and seemingly ignore energy demand and why that demand exists. While op-ed pages across the country today will raise concerns about climate denial in response to the release of the latest IPCC report, demand denial should also be a topic for discussion.

In fairness, IPCC does reference carbon capture in its latest report:

B.6.3 Global modelled mitigation pathways reaching net zero CO2 and GHG emissions include transitioning from fossil fuels without carbon capture and storage (CCS) to very low- or zero-carbon energy sources, such as renewables or fossil fuels with CCS, demand-side measures and improving efficiency, reducing non-CO2 GHG emissions, and CDR.

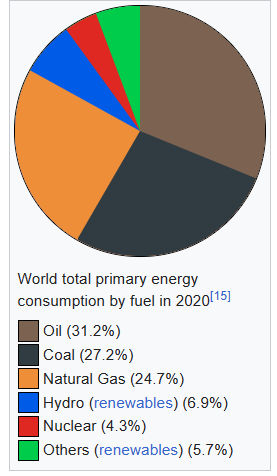

However, given the realities of global total energy source consumption, one might think that IPCC would push carbon capture harder, and that environmental groups would support advancing the technology. Simply put, there is no chance of meaningful global emissions reduction without robust carbon capture storage technology.

Global Total Primary Energy Sources:

Those who set emissions targets and deadlines should be more involved and accountable for executing an actual plan to achieve the goals they set. Guterres’ decision to move the goalposts by a decade demonstrates global climate leadership that is completely out of touch with the realities of global energy demand. The conditional optimism expressed in the report and by Guterres defies the realities on the ground. We will miss the IPCC climate targets.

Does that mean we should all surrender to alarmism? I will leave that question to a climate scientist and co-author of the latest IPCC report:

“We are not on the right track but it’s not too late,” said report co-author and water scientist Aditi Mukherji. “Our intention is really a message of hope, and not that of doomsday.’’

Scientists emphasize that the world or humanity won’t end suddenly if Earth passes the 1.5 degree mark. Mukherji said “it’s not as if it’s a cliff that we all fall off.”

John P. Grant is the Founder of Diogenes Group of Washington. The opinions expressed are his own. To contact John, visit www.DGWashington.com or email him at John.Grant@DGWashington.com